Understanding is often assumed to be a matter of accumulation: more information, more diagrams, more experience. In practice, it is something else entirely.

Systems rarely disclose their nature directly. They reveal themselves indirectly—through limits, failures, and the consequences of earlier decisions. What follows is an attempt to clarify this difference.

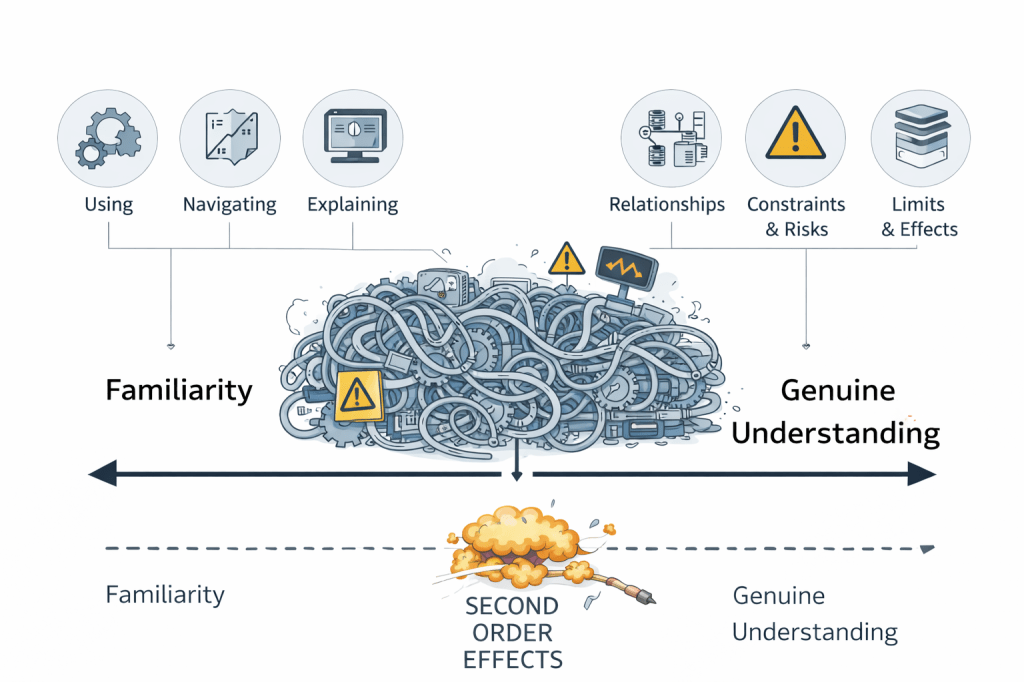

Familiarity Is Not Understanding

We often claim to understand a system when we can use it, modify it, or explain how it works. In technology especially, familiarity is frequently mistaken for understanding. The ability to navigate interfaces, deploy components, or recite architectural diagrams is taken as evidence of comprehension.

Yet systems reveal their nature not in normal operation, but at their limits—when assumptions fail, when interactions compound, and when decisions made long ago surface as constraints in the present. To understand a system is not merely to know its components, but to grasp the relationships, trade-offs, and boundaries that give it coherence.

Understanding begins where description ends.

Description, Use, and Explanation

A system can be described in terms of its parts: services, databases, APIs, processes, roles. This kind of knowledge is necessary, but it is incomplete. Two people may describe the same system accurately while understanding it very differently. One sees a collection of mechanisms; the other senses a living structure shaped by history, constraints, and incentives. The difference is not in information, but in orientation.

Using a system does not require understanding it. Many systems are explicitly designed so that users do not need to understand them. Nor does changing a system guarantee understanding. It is possible to add features, refactor components, or optimize performance while remaining blind to deeper structural tensions.

Even explaining a system—drawing diagrams, writing documentation—can be done mechanically, without insight into why the system is the way it is.

Understanding Reveals Itself at the Limits

Understanding shows itself in subtler ways.

Someone who understands a system knows what it cannot do. They sense where flexibility ends and rigidity begins. They recognize which changes are cheap and which are irreversible. They anticipate second-order effects, not because they can predict the future, but because they understand how forces propagate through the structure.

This kind of understanding is inseparable from limits. Every real system is shaped as much by what it excludes as by what it enables. Constraints are not incidental; they are constitutive. Performance ceilings, coupling points, organizational bottlenecks, cognitive load—these are not flaws to be eliminated, but realities to be worked with.

A system without constraints is not a system at all.

Convenience Can Obscure Structure

In software, this distinction becomes especially important. Modern tools make it easy to assemble complex systems quickly. Abstractions hide detail, frameworks provide defaults, and infrastructure scales on demand. These are genuine advances. But they also make it easier to mistake convenience for comprehension.

A system may function smoothly while its underlying tensions remain invisible. Latency is masked by caching, coupling by orchestration, fragility by redundancy. Over time, these hidden structures harden. What began as a flexible design becomes a set of implicit commitments. The system continues to run, but its freedom of movement diminishes.

True understanding often arrives late—when change becomes expensive, when failure modes multiply, when the system resists intentions that once seemed reasonable.

Systems Beyond Software

This pattern is not unique to software. Organizations are systems. Learning processes are systems. Even personal habits form systems with feedback loops and constraints.

To understand an organization is not to memorize its org chart or policies. It is to grasp how incentives shape behavior, how information flows, and where decisions actually get made. To understand a learning system is not to know the syllabus, but to recognize how attention, repetition, and feedback interact over time.

Across domains, the pattern repeats: understanding is relational, not additive. It is not obtained by accumulating more facts, but by seeing how elements condition one another.

Experience Does Not Guarantee Understanding

Experience alone does not ensure understanding. Time spent inside a system can deepen insight, but it can also normalize dysfunction. Proximity breeds familiarity, not necessarily clarity.

Understanding requires distance—a capacity to step back and see the whole, including oneself, as part of the system. Without this distance, even long experience can remain operational rather than reflective.

Responsibility and Restraint

There is a moral dimension to understanding. Systems shape outcomes, often in ways that are invisible to those operating within them. Decisions taken at the level of structure can have consequences far removed from their point of origin.

This is why mature judgment often appears cautious. It is not indecision, but awareness. The more deeply one understands a system, the less eager one becomes to intervene casually. Changes are made with an appreciation for what might be disturbed, not just what might be improved.

Understanding, in this sense, is closer to humility than to mastery.

Understanding as Orientation

In a culture that prizes speed, optimization, and visible output, this kind of understanding can appear slow or abstract. But systems do not reward haste; they reward coherence. Over time, shallow interventions accumulate cost, while well-considered decisions compound quietly.

To understand a system is to see beyond its surface, to live with its tensions, and to act with restraint informed by insight. It is less about knowing how to make things happen, and more about knowing when—and when not—to try.

Leave a comment